Almost twelve years ago to the day, Timothy Ray Brown, known for years as “The Berlin Patient”, was cured of HIV. He is the only person in history to have that distinction. That is, until now.

For just the second time since the global AIDS epidemic began, a patient appears to have been cured of HIV. “The London Patient”, who wishes to remain anonymous, stopped taking his antiretroviral medications in September 2017 and has remained virus-free.

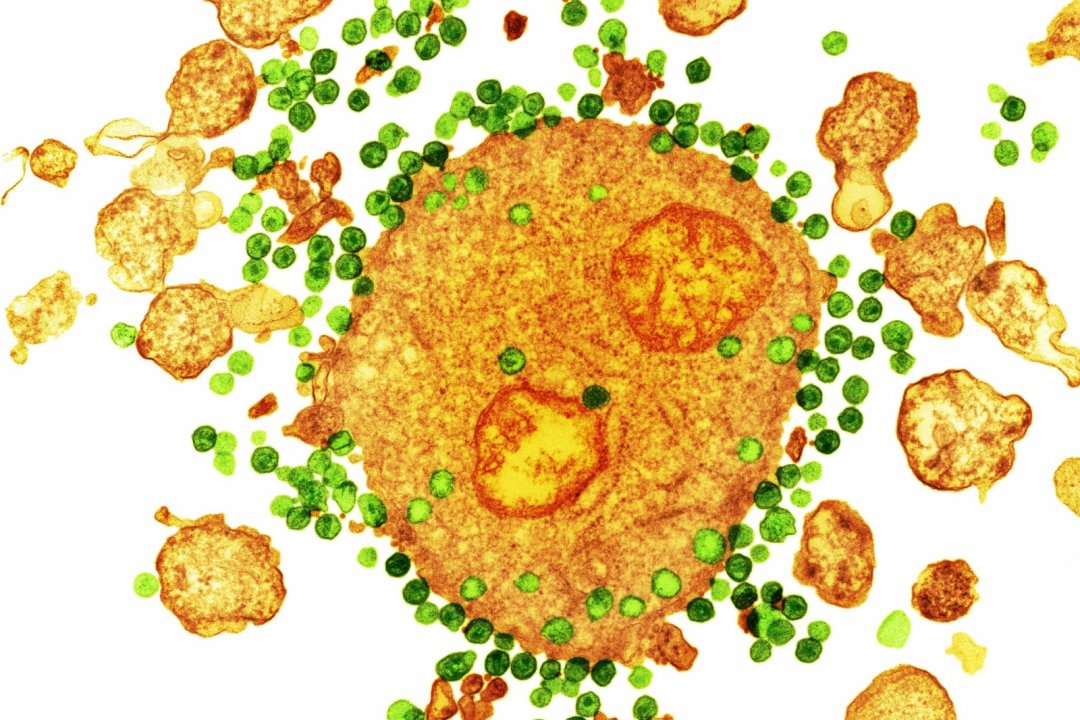

Both his and Timothy Brown’s cures were results of bone marrow transplants from donors with a mutation in a protein called CCR5. This protein, which is connected to certain immune cells, is exploited by the HIV-1 virus to infect the human body. A small number of people, mostly of Northern European origin, have a mutation in CCR5 which blocks HIV from infecting their immune cells.

One such person donated their bone marrow to Timothy Ray Brown twelve years ago, and another to “The London Patient.” With their old immune cells essentially replaced by those of the marrow donors, both men’s bodies are now able to resist the HIV-1 virus on their own, without the aid of antiretroviral drugs.

“The London Patient” demonstrates that this method of cure does not necessarily have to be life-threatening. Timothy Ray Brown, who had leukemia, was given harsh immunosuppressive medications and almost died after his bone marrow transplant. By contrast, “The London Patient,” who had Hodgkin’s lymphoma, was given less intense drugs and suffered few complications. However, it appears that, like Brown, all of his HIV-vulnerable immune cells were replaced by the donor’s HIV-resistant cells.

Although both Timothy Ray Brown and “The London Patient” were being primarily treated for cancer, their unique method of cure may still be useful for cancer-free people living with HIV. For example, it may lead researchers to explore different types of gene therapies that directly target the CCR5 protein, or introduce a stem cell that is HIV-resistant and can duplicate naturally in a person’s body.

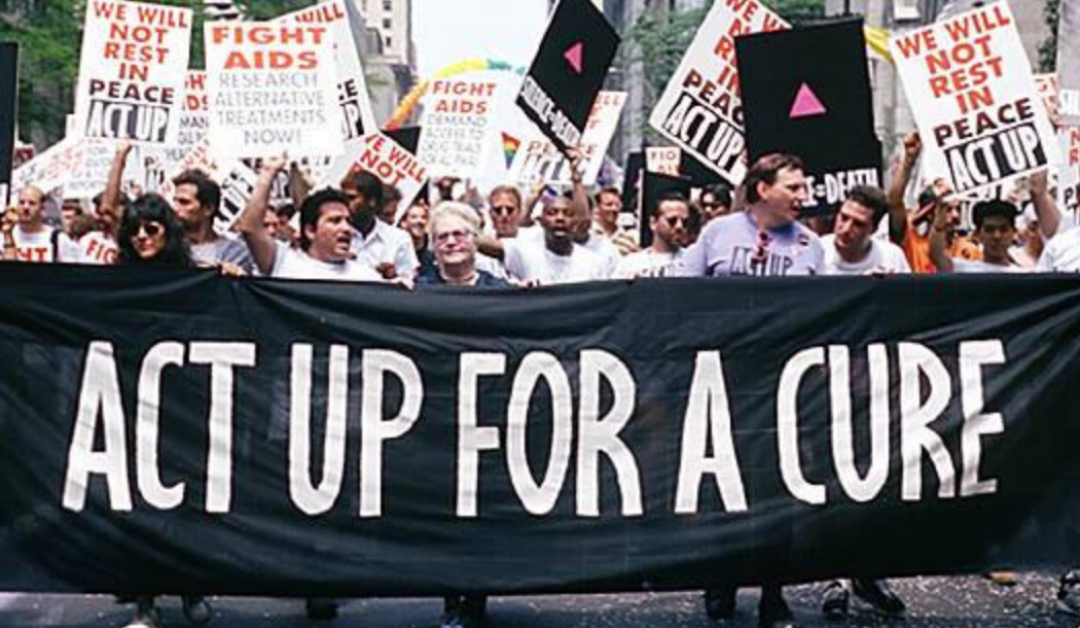

All of these approaches have challenges and caveats. For example, a form of HIV called X4, which uses a different protein to enter cells, could still attack the body of a person with a mutated CCR5 protein. Nevertheless, “The London Patient” offers several promising new avenues for research. And more importantly than that, he keeps the dream alive that one day, perhaps in our lifetimes, a cure for HIV will be developed. The AIDS epidemic will always be a part of our past. But it doesn’t have to be part of our future.

For more information about “The London Patient”, check out The New York Times article here.